2378 words // 13min read time

Hello, fellow creative! Today, I’m going to share a book review/report with you. I look forward to sharing many titles in these reports and connecting them to my Creative Journey Series. I believe as creatives it is so important for us to study the works of others, and use the creative tools that other artists have provided. Seeing the field of art through many perspectives and lenses is crucial to growing ourselves as artists.

Whether you purchase these books second-hand, or check them out from a library, I can say that I recommend perusing them, taking them in, and processing their contents. I like to purchase them second hand and see the underlining, highlighting, and notes in the margin from the previous owner. Plus, reduce, reuse, and recycle!

Sometimes I will review a book that is written by an author who means to help us with our art, and sometimes I will review a curated art book that has a few editors and focuses on the artworks of a certain artist. In both cases, there is something to be learned and inspiration to be gathered.

Without further ado, I present:

–

Why This Book?

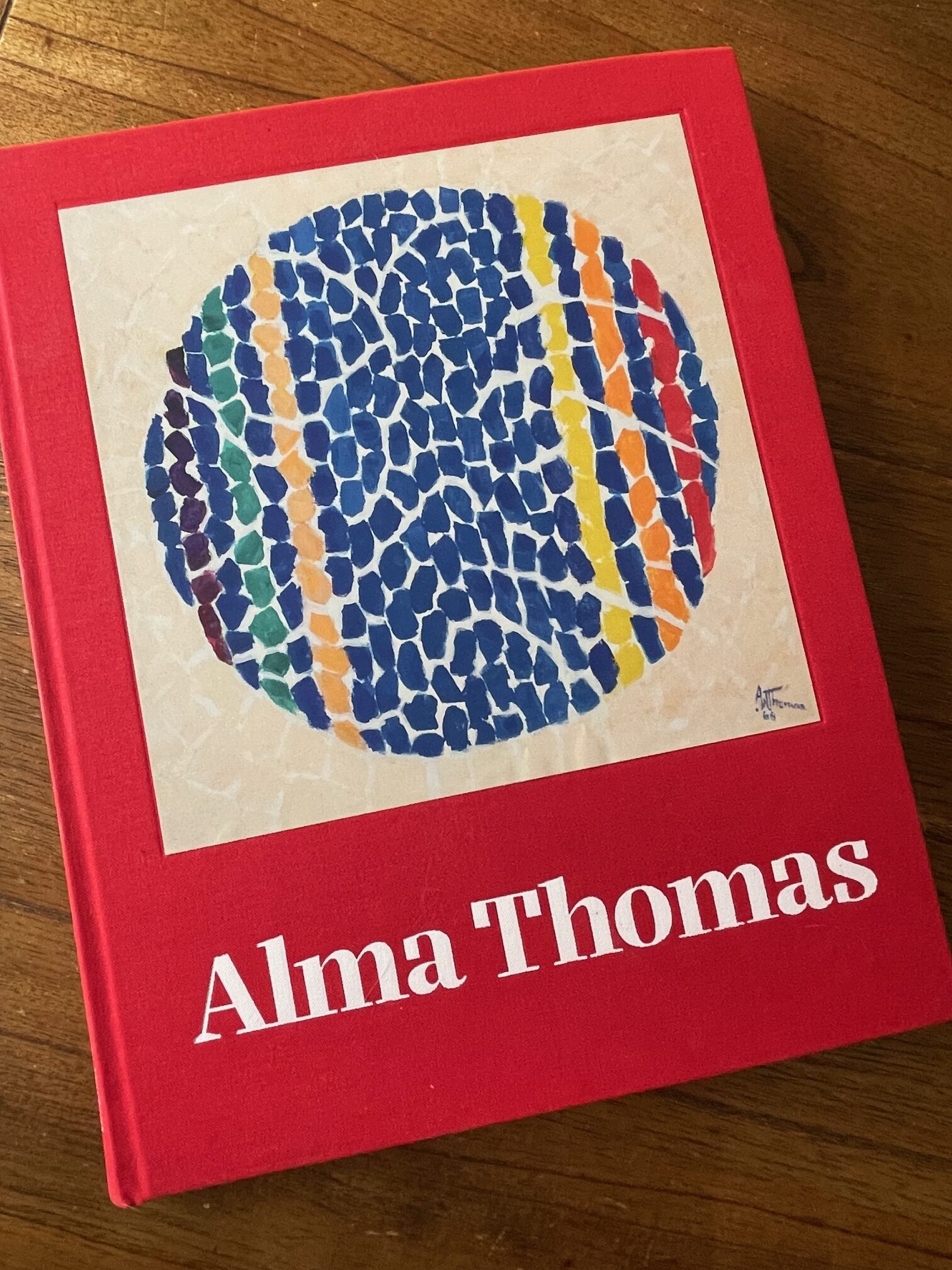

I chose Alma Thomas at a moment when I needed to remember that the middle of the creative journey can be the most vital, even though it’s often messy, uncertain, and full of reinvention. Thomas’s story is a beacon for anyone navigating the long road toward authenticity. I was drawn not only to her joyful, mosaic-like paintings, but to her resilience and reinvention. This book called to me as both an artist and a woman living in layers, as a wife, mother, and creator, and it felt especially aligned with the part of my journey where doubt gives way to depth.

This book aligns perfectly with my creative journey’s second phase, especially in moments of surviving the messy middle. You can read more in the Part 6 blog post.

–

About the Author/Artist

“I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People struggling, having difficulty. You meet that when you go out, and then you have to come back and see the same thing hanging on the wall. No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at. And then, the paintings change you.”

– Alma Thomas, ca. 1977–78

Alma Thomas was a teacher and artist who developed a powerful form of abstract painting late in life. From the mid-1960s, she produced brilliantly colored and richly patterned works intimately connected to the natural world.

Thomas was raised in a household that emphasized culture and learning. In 1907, her family moved to Washington, DC, in search of greater educational opportunities and relief from racial violence in the South. In 1924, Thomas became Howard University’s first fine arts graduate, encouraged by the art department’s founding professor, James V. Herring. She then began an esteemed thirty-five-year teaching career at Shaw Junior High School. In addition, Thomas earned an MA in arts education at Columbia University in 1934 and studied art at American University during the 1950s. A significant figure in Washington’s art world, Thomas was associated with the Little Paris Group of artists and Howard University’s Gallery of Art. She was also instrumental in the 1943 formation of the cutting-edge Barnett Aden Gallery, among the first Black-owned galleries in the United States.

A talented representational artist, Thomas moved toward abstraction in the 1950s with works like The Stormy Sea (1958, SAAM), but she arrived at her signature style only after retiring in 1960. Spurred by the prospect of a 1966 exhibition at Howard, Thomas began painting with small daubs of vibrant colors arranged in rhythmic patterns, as in Light Blue Nursery (1968, SAAM). With these works, she charted a new path, inventively drawing on artistic practices ranging from French twentieth-century artist Henri Matisse and Bauhaus artist and color theorist Johannes Itten to local artists and peers, including painter and Howard professor Loïs Mailou Jones and abstract painters of the Washington Color School. Thomas consistently found inspiration in nature, as in paintings like Aquatic Gardens (1973, SAAM). Washington’s parks, the garden beyond her kitchen-studio, and memories of roses around her childhood home all proved vital touchstones. Scientific advances, especially early space travel and the new vantage points of Earth it afforded, also impacted Thomas’s work, as in Snoopy–Early Sun Display on Earth (1970, SAAM). Though Thomas attended the 1963 March on Washington, creating three related works, her practice and its attention to color did not overtly engage the civil rights movement. Instead, she emphasized beauty’s restorative power: “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.”

Thomas’s post-retirement paintings earned tremendous critical praise—no small feat for an artist outside New York City. In 1972, she became the first Black woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, presenting The Eclipse (1970, SAAM) and Antares (1972, SAAM), among others. Around then, Thomas reflected on her segregated childhood: “One of the things we couldn’t do was go into museums, let alone think of hanging our pictures there. My, times have changed. Just look at me now.”

Authored by Katherine Markoski, American Women’s History Initiative Writer and Editor, 2024.

–

Their Websites and Links

Overview and Core Themes

Reading about Alma Thomas redefined my relationship with time. Her life reminded me that creativity is not a race, and that every stage feeds the work to come. As a maker who also juggles caregiving and teaching, I felt seen. Her method of working in iterative circles of color mirrors my own attraction to modular and meditative motifs. I also noticed how she let her environment shape her palette. Whether it was the way light moved through trees, or the view from her window. It encouraged me to look closer at my own surroundings and how they show up in my designs.

Core Themes:

- Alma Thomas began her professional painting career in her 70s, after retiring from decades of teaching art. That alone is revolutionary.

- Her work exemplifies how joy, color, and abstraction can be a political act, especially for a Black woman artist working in segregated Washington, D.C.

- Thomas was deeply rooted in process, repetition, intuitive play, and the subtle evolution of form.

- She wasn’t interested in realism or protest art. Her resistance was in her radiance, and choosing joy was her artistic stance.

- The book shows how late bloomers, educators, and caretakers are not outside the creative story.

A Sample of the Chapters

Here are some of the chapters and a short summary.

This exhibition catalog was edited by Ian Berry, director of the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College. The volume gathers voices from curators, scholars, and artists to explore Alma Thomas’s life and legacy in a rich, multifaceted way. The text moves between biographical details, formal art analysis, and cultural reflection—blending historical rigor with deep admiration. The point of view is celebratory but grounded, placing Thomas in her rightful place within both the modern art canon and the broader Black artistic tradition.

There are four major chapters that outline Thomas’s work through the decades: Move to Abstraction, Earth, Space, and Mosaic. In between the showcases of her art, there are essays about her rich and robust life story.

Here is a piece from “Move to Abstraction.”

–

Aha Moments & Favorite Quotes

“A world without color would seem dead.” – Alma Thomas. This quote captures her worldview perfectly. Color was her life force. Creative art is for all time and is therefore independent of time. Thomas often saw herself as part of a lineage that transcended era or trend. This helped me trust my own slower pace.

Another moment that stayed with me: the image of Thomas painting in her home studio, standing at her window, watching the world in motion, then translating it into joyful abstraction. There’s something holy about that rhythm.

Here’s a piece from the “Earth” chapter.

–

And a piece from “Space” – maybe my favorite chapter.

–

And then a piece from “Mosaic.”

–

Author/Artist’s Purpose

Alma retired from Shaw Junior High School in 1960 at 69. She began painting full-time, making large-scale color field paintings that demonstrated an interest in color theory and were influenced by the New York School and contemporary Abstract Expressionists. Her first retrospective exhibition was in 1966 at the Gallery of Art at Howard University. In the lead-up to the show, she fine-tuned her use of rectangular shapes and rich colors. Alma’s layering of colors in concentric, almost meditative patterns was well received, and the show gained her local recognition and critical support.

Alma’s art was nationally recognized, and she became a touchstone for both the feminist and African American artists who would follow her. A central figure in American Modernism, several of Alma’s pieces were chosen by the Obamas to display in the white house during both terms. In 2014, her painting Resurrection (1966) was acquired by the official White House Collection, making it the first artwork by an African American Woman to enter the permanent collection.

Some of my favorite works:

Although a Black woman would not travel to space until Mae Jemison was on the Endeavour in 1992, Thomas insisted that when she painted, she was with the astronauts. She said, “My Space paintings were inspired from the heavens and stars and my idea of what it is like to be an astronaut exploring space.” source

Alma Thomas Spring Flowers in Washington D.C. 1969, Oil on canvas | Private Collection, Pasadena, California (acquired directly from the artist, 1969)

–

Through her work as an educator, Thomas was envisioning the future. She said, “People always want to cite me for my color paintings, but I would much rather be remembered for helping to lay the foundation of children’s lives.” One of the primary tenets of Afrofuturism is black liberation. Thomas was using her work as a statement of possibility—as a place to which she could go to get away from the cruel world of segregation and oppression that she inhabited. She was leaving all that behind in hopes of a liberated future. Furthermore, by engaging with the space race, she was making an implicit, yet bold, political statement about Black people’s role within it. This is the significance of her performance as an astronaut: her refusal to let white supremacy confine the boundaries of her art, life, and career, instead expanding them to the entire universe and taking her students along for the ride. source

Alma Thomas, “Apollo 12 Splash Down,” 1970 (acrylic and graphite on canvas). | Courtesy of Michael Rosenfield Gallery, New York. Courtesy Studio Museum in Harlem

–

Alma Thomas, Snoopy–Early Sun Display on Earth, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 49 7⁄8 x 48 1⁄8 in. (126.8 x 122.1 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Vincent Melzac, 1976.140.1

–

Creative and Artistic Takeaways

Inspired by Thomas’s signature technique, try this:

Choose a view from your everyday life, whether it’s your backyard, a favorite park, even your kitchen table. Instead of sketching it literally, break it down into shapes and colors. Think in dashes and dots. What colors dominate? How does the light move? Then interpret that into a motif, a swatch, or a color map. It’s not about accuracy, it’s about mood. Let the rhythm of your hand guide you, and embrace imperfect repetitions.

Some more nuggets of wisdom:

I just love this. It seems like Alma Thomas was very much her own woman and didn’t bow down to anyone. Its so inspiring how she focuses on protecting her peace in such a tumultuous world.

–

Visual Impact

Alma Thomas’s visual language is built from strips and dashes of saturated color, often in radiating or gridded forms. She worked almost exclusively with pure hues like vibrant reds, piercing blues, and high-energy yellows, and she laid them down like musical notes. The effect is rhythmic, almost symphonic. Her compositions balance spontaneity with structure, embracing slight imperfections and handmade edges. She never masked her brushstrokes or fussed over symmetry. The beauty was in the pulse. Her approach made me think of how I build texture and rhythm in crochet, how even the smallest variation can shift the mood of a motif.

–

Final Thoughts

Would I recommend it? Absolutely. This book is essential for anyone looking to reconnect with joy, process, and color. Especially women, late bloomers, and artists of any medium navigating self-doubt. It’s part inspiration, part validation. The only limitation is that it’s very much an exhibition catalog, so some sections lean scholarly or archival. But even that deepens its richness. I’d recommend it to creatives who appreciate both visual analysis and human stories.

Alma Thomas, by Ian Berry (Amazon)

–

Thanks so much for checking out my analysis of this book. The free crochet motif that goes along with this book report will be released soon! Hope you have a great week, and happy crafting!

Rachele C.

Order my crochet pattern book: The Art of Crochet Blankets

You may also enjoy:

Support My Work

You’re supporting by just being here! You can read my blog (Start Here!), like and comment on socials, and message me for a chat. All of this supports my work free of charge!

- Affiliate links – Shopping through my links supports me at no additional cost to you as I get a small commission through my affiliates. Jimmy Beans Wool // WoolWarehouse // Amazon.com

- Buy my pattern book – I wrote a super neat crochet blanket pattern book, published under Penguin Random House. You can buy it here!

- Browse my self-published patterns – I have over a hundred patterns on Etsy //Ravelry//My Podia Shop

- Creative Art Blanket Course – Check it out on Podia

Where to Find Me

- Instagram: @cypresstextiles

- Facebook Page: CypressTextiles

- YouTube Channel: Rachele Carmona

- Pinterest: CypressTextiles

- Tumblr: CypressTextiles

- Etsy: CypressTextiles

- Ravelry: Rachele Carmona

- Podia: Creative Art Blanket Course